Links

- Figma Prototype 2

- Figma Prototype 3

- Class Final Presentation Slides

- Design Journal with all project milestones

Subset of Final Paper

Over the last few decades, global research infrastructure has been enhanced to include unique identifiers for journal articles and then people, organizations and many of the supporting research outputs like datasets, software. While this may seem mundane, these identifiers make it possible to disambiguate, to give credit by citing scholarly outputs, people and institutions and most importantly to create a bibliographic network that allows discovery through these connections. Many journals now require that data and software are published in repositories and accessible with the publication. This development has led many universities and large research organizations to develop institutional repositories to house research outputs including open access copies of journal publications, theses and dissertations, and a smaller number of datasets and software. However, despite these parallel developments with the ability to create connections through identifiers and the creation of institutional repositories, institutional repositories do not use identifiers and thus, aren’t showing up in the global research infrastructure.

Driving Questions

The driving question for this project started as: How might institutional repository staff contribute research objects to the global identifier infrastructure?

This driving question evolved and broadened through my initial user research to: How might repository staff, such as data curators, contribute and connect research objects to the global identifier infrastructure? This update came from my user research where interviewees shared that they were not just interested in contributing research objects, but they were also interested in or already creating connections in their metadata to search for identifiers and link related objects or people and organizations. In addition, in the original question I didn’t want to narrow the staff definition until I’d had some user interviews. In the second question, I knew that the title of these people was data curators, so I included that here.

As my teammate, Ted Habermann, and I discussed what I’d learned from the user research, we realized that there are really several different questions wrapped up in the original question: how to find identifiers for people and organizations at creation? how to find DOIs being used in journal articles and other scholarly publications? and how to add related works to those dataset records? This topic of people identifiers came up again and again in user research, it is currently a tedious task to add the identifiers and it seemed like it would provide significant benefits to both curators if we could make it easier and researchers contributing these objects as well. We used this question for ideation and for prototyping. We chose to narrow from the broad question of general contribution and connection to the global research infrastructure to: How might we find identifiers for people (ORCIDS) during the metadata creation process?

It was exciting to me that the questions followed the first part of the diamond with the first iteration being more narrow, then the midpoint question was more expansive and the third iteration of this question narrowed the scope considerably and didn’t try to solve the entire global challenge, but focused on one specific part of the workflow like the double diamond diagram that we have been working with.

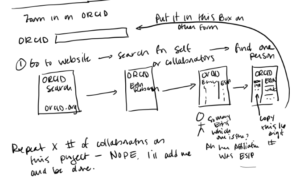

Figure: This figure shows the current story map for how researchers have to manually fill in their ORCID

User Research

I conducted eight, unstructured interviews with data curators at institutional repositories. The interviewees were recruited from Twitter (tweet) and LinkedIn (post) and through an email to the Data Curation Network. The interviews lasted about 40 minutes and followed these general questions:

- Background of the person I’m talking to

- How do they curate data

- What tools, standards does their repository use

- What challenges to linking to global infra

- What benefits to linking?

- Anything else they would like to share?

When I started this project I was interested in institutional repositories’ willingness to update their metadata records with identifiers, so I hoped the interviews would uncover motivation for updating records and challenges to using identifiers and participating in the global identifier infrastructure. I complimented these interviews with secondary research by further defining the problem of adding identifiers and integrating with the global identifier infrastructure for research data. My interviewees were the best source of secondary sources to include talks they had given, white papers and blogs from organizations like ARL and journal articles.

I hoped the combination of these methods would uncover patterns in the way curators describe the problem of adding identifiers and updating metadata records and that it would reveal causes of these problems and consequences. Some themes that emerged included the following:

Theme 1: Metadata (or data model) Challenges

Linking to the Global Research Infrastructure is often a challenge for institutional repositories because of metadata challenges. Data and science friction are related to issues with incomplete metadata. This connects to the interview data that over and over pointed to limitations or friction with their metadata models (Edwards et. al, 2010). There is a lot more data from interviews that repeats the sentiment of Interview 1.

[Interview 1] The problem is the metadata model, if I’m thinking about it, yeah, I don’t know where to put all that citation information. So okay, let’s say we discover that a datasets been cited four times five times? Where do I put it? Where do I store that information? It’s not in the record.

Theme 2: Creating Connections with Identifiers

There is really exciting work being done to show the value of creating connections and leveraging the global research infrastructure. Two examples show both automatic and manual connections.

USGS Publink searches a corpus of publications for the DOI, the exact title and DOI prefix as ways to identify publications that are citing USGS datasets. When Publink finds these publications, it then updates the DataCite dataset metadata for the record to make the connection complete. When a user comes to the landing page for that dataset after this, they will see the paper that listed the dataset DOI in a list of related work. The image below shows the updated metadata.

Interview 2 also shared a vision and initial example for the Extended Specimen Network. However unlike with Publink, the initial example of the extended specimen. Interview 1 mentioned searching for DOIs by hand as well.

[Interview 2] And so the facilities are all there to create those linkages, but it’s all human modulated, where I have to go in and I have to make those connections myself, because the sort of technology doesn’t exist to link those things together using persistent identifiers,

Theme 3: IRs focused on Data Reuse | Very involved curation

Two interviews were conducted with informants that were highly involved in the curation process and that ensured rich metadata and documentation. This interview excerpt gave insight into the curation process when data reuse is the goal.

[Interview 1] But very, very short. We assign it to a data curator, and they work with that researcher to ensure that the data are we aim for reusable, reusable. … Reusable is inclusive of can I understand this data? Can I can I actually? Do I know what the variables mean? Do I understand the file formats? Can I open those file formats? Are they open? You know, we’re really trying to figure out is there enough documentation and evidence in that dataset. And native to that dataset, we really don’t appreciate it when researchers just say, Oh, we’re the paper. We really try to bring it all together.

Theme 4: Institutional Repositories focused on data providers

A counter to theme 4 also emerged that some repositories are just interested in contribution and not in reuse or connection to the broader research infrastructure. A set of interviews shared that their repository’s purpose was for data producers. The quote from Interview 3 shows that when the repository purpose is designed for ease to contribute instead of reuse.

[Interview 3]: “So when they set this up, originally decided how the it was the first real like public facing system for getting content in, there was a faculty advisory board to give opinions about how the system should work. And the faculty Advisory Board’s priorities were to have a place that was easy to put this content that they needed to share related to publications, it is not driven by a lot, the library’s desire to develop a repository of high quality datasets.”

From this user research, I developed two personas: (1) a technical, hands-on curator who is augmenting his collection and building his own network through connections and (2) a non-technical, institutional repository manager who needs there to be a streamlined process for metadata included to provide for reuse and allow her to make the case on the return on investment the institution is getting to do this extra work. These personas then informed the solution space that we ideated on. Below are some quotes from the user research that supported the final design question.

In the interview data, interview 1 said there wasn’t any ID linked to the records.

“Um, the problem there is it gets back to our metadata problem with with ORCIDs and not having not having a person ID associated with the records.”

In interview 4, they expressed that there had been so much demand for a space to add ORCIDs that they had ‘hacked’ a way to do that. This quote describes that hacking and interaction with users:

“So what we did is we sort of did a did an investigation of our metadata schema and looked at fields that might fit as sort of an ad hoc ORCID Identifier field, and then made sure they were being used in any other parts of the forum, or you have very low usage rate. And we actually found a metadata element in the DCE, in the Dublin Core schema that worked for us to just say, like, Okay, we’re gonna put ORCID data here, and we’re gonna label it in the interface. So that it says author ORCID, right? We then told the our partners like this is here, you can start entering ORCIDS, with some caveats. One, this is 100%. Ad hoc, we don’t have this isn’t pulling ORCID data from orchid. This is you entering a text string. And we are all agreeing that this is going to be an ORCID. And this is how you have to do it. And if you don’t do it this way, the functionality is going to break. And we make no guarantees that all this is going to integrate with the next version of D space, which is D space seven. But it might make it easier for us to look at a full ORCID integration with the next version. Yeah.”

Reflecting on this process at the end of the project, the interviewees were people I could have talked to for much longer and while the open ended, unstructured format let the conversation go in interesting directions for this kind of design work and knowing how the rest of the process continues, I wish I’d targeted the questions more to identifier usage, challenges and to this idea of updating metadata records with identifiers.

Evolution of Prototype

With my partner, we brainstormed several possible solutions to our questions from the current, tedious solution of searching by hand to thinking about several ways that we could respond to the user research and streamline this process.

Next Steps

The big idea that emerged in this project is that there could be additional useful information like known collaborators that is linked to the ORCID profile and accessible in other places like institutional repository metadata. This would allow a user to reduce redundant entry and to connect more easily to the global research infrastructure.

In next steps, I would bring this prototype 3 to the users that I interviewed originally and use it as a design probe and conversation piece to identify how they might incorporate this into their current workflows. If their general sentiment was positive, it would be interesting to build a higher fidelity working prototype that utilizes the ORCID API to test this prototype with a broader set of tasks. Through this round of design, I dropped the idea of updating existing metadata as I moved through this UCD process. I would take this task back to usability testing. The thing I would spend the summer with is on building out the known collaborator network graph prototype. I would build out the graph and experiment with ways to show that to the user who is picking collaborators.

In this round of UCD my initial question was so broad before I did user research and after user research the question broadened even more, at times feeling overwhelming and hard to narrow. In the future I would narrow the topic before going through the UCD process so that I could have more targeted user research – all persistent identifiers were way too broad. What would my process have been like if I’d narrowed right away on a single kind of identifier like ORCIDs for people? I’d also like to get better at more out of the box thinking and bringing in inspiration from other areas b/c while I’m happy with where I got with this work it felt hard for me to really stretch and think of things that don’t actually make sense. I might take existing things that work and make them bad or use some of the techniques we tried in class towards the end of the semester to apply alternative ways of thinking.

Reflection on Learning

At the beginning of the class, I included in my design journal several things that I wanted to learn. I felt like I had never had a clear design education. Re-reading that I think I meant I wanted to formalize my design education and through the systematic thoughtful structure of this class I feel like I made progress on this goal. I thought at the beginning that I would feel proficient at the end of this class and more than anything I learned that design is a practice and I need to keep practicing. To that end, I wanted to consider design principles in my other research projects and that has happened over the semester and will be part of my on-going practice. I shared Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process with several of my collaborators. I appreciated that it helped me break the habit of just saying “I like… “ and staying at a superficial level. I also appreciated that this process put the control back into the designer’s hands to control the feedback process. I have used this in seminar discussion and when I give feedback. At the beginning of the semester I said I wanted to learn from others instead of just trial and error myself. I learned from reviewing other’s design journals in our class and picked up ideas and new ways of thinking and understanding the material we were working on.

Finally, there are two things that have been extraordinarily powerful. The first was the work that we did on positionality, power and critically considering design. Understanding the biases and the ways that power is wielded in everyday objects is eye opening and has made me a more critical observer and added new ways that I think and question information infrastructure. The second thing that I am grateful to take out of this class is to create and just get started and get messy. I loved the sketching exercises and parts of the design process and for me the highlight of the project was the fifth sketch (fig 3) where this entirely new idea popped out! I am excited to build my design skills and carry this forward in future work. I would like even more design justice and critical theory brought into UCD.

References

Edwards, P. N., Mayernik, M. S., Batcheller, A. L., Bowker, G. C., & Borgman, C. L. (2011). Science friction: {Data}, metadata, and collaboration. Social Studies of Science, 41(5), 667–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312711413314